Font-Size

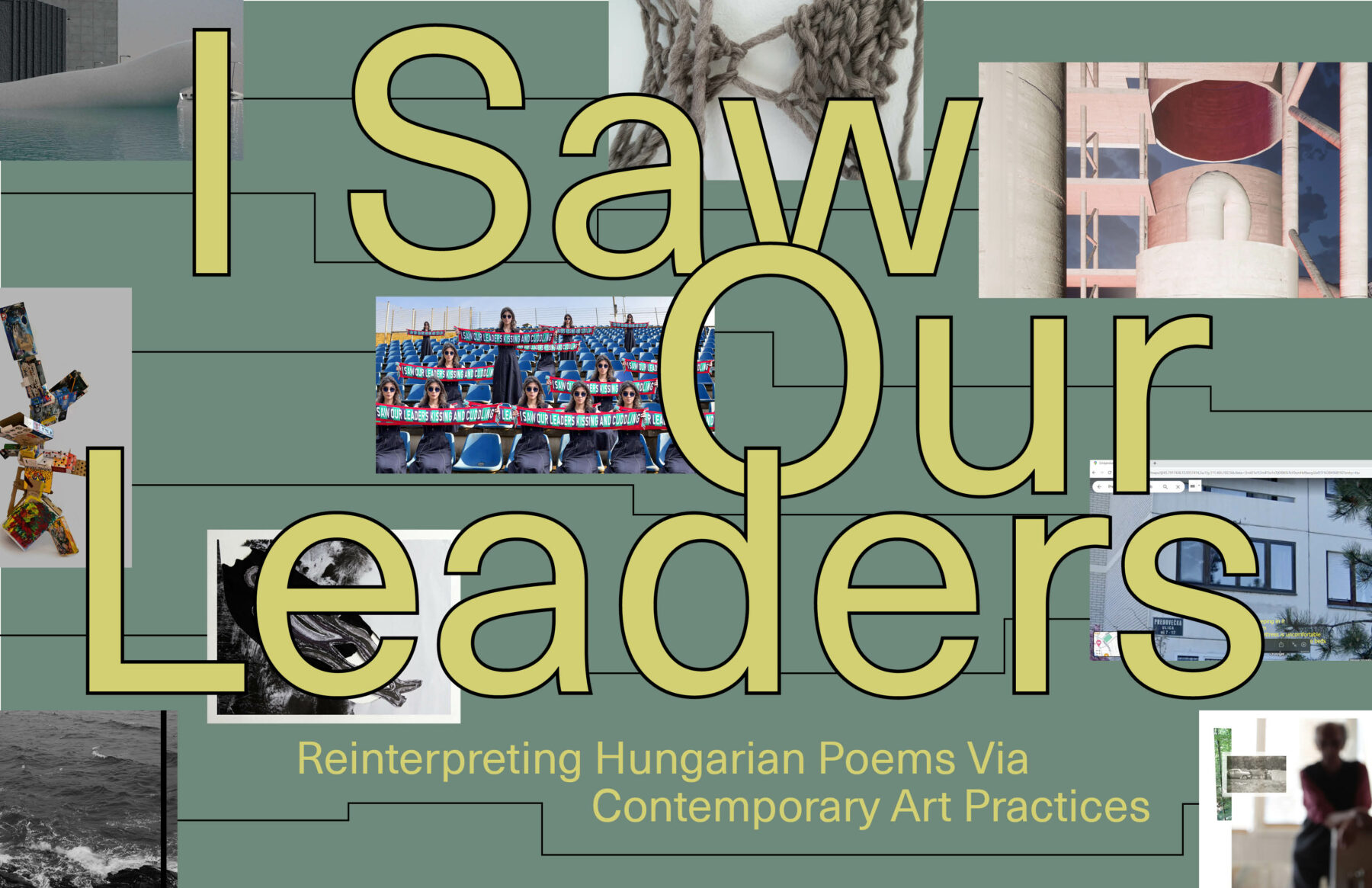

I Saw Our Leaders

Reinterpreting Hungarian Poems Via Contemporary Art Practices

Since the founding moment of the European Alliance of Academies in 2020, the Hungarian Writer’s Organisation Szépírók Társasága (Society of Hungarian Authors) has been a vital member of the transnational network.

In the beginning of 2023, the National Cultural Fund in Hungary cut the annual subsidy of the largest independent Hungarian writers‘ organisation by a third. For 2024, the organisation will receive no funding at all. There is no doubt that the Hungarian government aims at eliminating local independent civil societies. Against this background, the European Alliance of Academies decided to support Szépírók Társasága by initiating a new project of artistic collaboration, based on a collection of nine poems by a young generation of Hungarian poets, all members of the Szépírók Társasága.

The selected poems address issues such as identity and otherness, migration and longing for homeland, and political authorities through a grotesque depiction of their privileged place. The shadow of Hungarian past is present in the turmoil of an anthropocentric landscape. Different imaginaries of homeland are infused by personal memories of and the desire to reconnect with nature.

Nine artists from across Europe – all associated to institutions of the European Alliance of Academies – engaged with the poems and created multidisciplinary artworks that respond, comment and reflect on the social and political reality of today’s life in Hungary. With their work, Yese Astarloa, Matei Bejenaru, Lucija Bogunović, Sayaka Fujio, Iosif Király, Paul Michels, Mariano Ortega, Dimitrina Popova and Laura Stojkoski add another layer of meaning to the poetry selection, thereby creating a pan-European artwork.

Several alliance members were involved in the design of the project. We would like to express our sincere thanks to Ferenc Czinki (Szépírók Társasága), Kristoffer Gansing (former International Center for Knowledge in the Arts – The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts), Anca Poterasu (Romanian Association for contemporary Art), Geertjan de Vugt (Akademie van Kunsten, Netherlands), Nikki Petroni (Arts Council Malta) and Josip Zanki (Croatian Association of Fine Artists).

Poets and Authors

- Round our way Róbert Laboda

- I saw our leaders Réka Borda

- Utter it in my stead Dénes Krusovszky

- Fiume in labour Ádám Vajna →︎

- Cement factory, autumn Mónika Ferencz

- Tender peas in a pod Zsófi Kemény →︎

- Border strip Renátó Fehér →︎

- Hungarians Balázs Szálinger →︎

- H Márton Simon

Poetry selection

Index

Róbert Laboda

Round our way

not even one

out of twenty

says hello

and even hello back

only rarely

as if every drip of brandy

washed not their guts

but their brains

my home Palócland

you’re forgetting me

and I miss you like the dug-up

cobbles that lead to the prison

beneath the castle grounds

your colour most

resembles the concrete

yard of my old school

where I first laid plans

for my life

and where they pollarded

the willows so their branches

wouldn’t meld with the tar

unike my former pals

who became to a man

grown-up grown-old

assembly line workers

ambling along sad

and poor

transparent plastic

carrier bag in hand

a grey image of the future

Réka Borda

I saw our leaders

I saw our leaders kissing and cuddling

under their neckties; the hot soup

went cold as they sealed the mouths of their herd,

while they wallowed in their palaces; a few of them,

woolly, followed him out onto the terrace

of the conference hall, and I’m sure I know

who smoked their cigar naked behind the shutters;

as they filed down, willy-nilly,

the columns in the afternoons, and had the workers

build concrete pyramids; in due course the youngsters

decorated the walls with hieroglyphs; according to legend

accursed were the buildings that the graverobbers

from time to time came to strip;

to mourn my grandfather’s lungs,

into which sand was sprinkled, and I saw

the desert sprawling over the hospital

with the cactuses that struck root

in throats and kidneys; from time to time

stormclouds swell between the lightbulbs,

and they water those that will die anyway;

to play with pinwheels while they held

their mum’s hand; and to sing about tulips

beneath the pleated skirts, in order to drown out

the folksong of those on the fence’s far side;

there are nights when our leaders retch side by side,

yet it’s the downstairs neighbours who suffer the smell.

Dénes Krusovzky

Utter it in my stead

A stranger was checking me out,

from his confused movements I can deduce

what I’d find in the collapsed hall

of the old rope factory. In the voice of

the lonely tools, lifted by chance and at once dropped back,

something utters what I myself

am unable even to think.

Sometimes I can’t imagine you, my homeland,

except as a damp shower curtain clinging

to my skin. Or as if I were resting one hand

in an empty nest, while in the other

I have already crushed the eggs. There are times

you don’t even cross my mind.

Ádám Vajna

Fiume in labour

Under the cafés’ awnings

The folk gathered in fine Fiume

Hastened once long ago

Seeking shelter from the rain.

The gaps between the cobbles

Began to fill with water,

While the folk eyed each other

To see who had badges on their chests.

The sea was five minutes’ walk away,

Yet no one wanted to go there,

Not really because of the rain, but because

They knew how easy it was to drown.

A cab for hire pulled up in the street,

It wasn’t easy to see who was in it,

The foul-mouthed coachman clambered down

To batter his chestnut bays.

Yet the whole thing had a kind of

Joyful fucked-up charm,

So that it seemed that the few dozen folk

Weren’t after all waiting for better weather.

Beneath the striped awnings crouched

The behatted, bechest-pinned horde,

And one girl amidst them already carried

Comrade Kádár under her heart.

Mónika Ferencz

Cement factory, autumn

From a window in my grandma’s house I watched

how the cement factory in Vác

stood motionless in the night.

I couldn’t yet have known that in other towns

it’s bridges and churches that are illuminated

in the way that here, up north, is the threatening

tower of concrete and frost.

That’s when my grandpa came in.

In his hands a see-through rosary, a token

of the eternal longing to depart or return.

I thought he was talking about my father,

but it turned out it was about God and the

misshapen animals with gouged-out eyes

living in the depths of the ocean.

He spoke, while I watched

the lights that concealed themselves behind him.

Meanwhile I subconsciously assumed

the rhythm of the breathing of

the 22-kilo man lying in the other room.

Finally my grandpa went out and locked

the door of the room filled with palm branches.

Silence fell. You could hear

that in the guts of the man lying in the house

death was stamping all eight of its feet

and realised: that too was just cement

and water; what of dust was made

will once again return to dust.

I pounded the concrete wall and had to admit

that my fist is of china made.

Zsófi Kemény

Tender peas in a pod

We are at the point where we left ourselves.

We’ll come back later. Until then we’ll start again elsewhere;

an innocent little game with our time.

We know how to deploy our face.

Get laid, little table, or my man!

Disclosure is our mentality,

and that’s something we deliberately rushed into.

Now they’ll be able to gloat and console.

As for us, we’ll have to weep if and when they console us.

We go to a concert so that we can leave;

the crowd is huge and the music too loud.

We rub each other’s noses

into one another’s grey everydays:

“see, things didn’t turn out any better for you,

even though you did medicine”.

Of course we’ll have better arguments than that.

Even we are just taking shape.

We watch our image in the looking glass,

while our pride waits outside.

We’d bow and scrape before anyone

more of an exhibitionist than ourselves,

yes, more of an exhibitionist!

Wherever we go, that’s our way, that’s what we stick to.

Sticking, that’s something we know how to do well, and being offended even more so.

This is how we play at being younger than our age.

And having become younger, we keep it up,

because if we don’t, they’ll realise how old we really are.

We have still to price in a few small matters.

We’d have liked a round anniversary,

but for years we have lived in gentle unions:

A good marriage leaves the deckchairs out in the rain,

a bad one brings them indoors.

We always reached whereever it was necessary

to get to, somehow or other.

We travelled, we shivered, and shared

big thoughts: what next, and how?

It’s no longer cold but we continue to shiver.

The solution? Oh, forget it.

We are painful for each other

yet without each other we lack a past.

We brought each other up, educated each other,

how can we now be on opposing sides?

We sit, little peas in the levered-open pod.

We would roll away. We can’t.

Love is no magic weapon, but it isn’t poison either.

We too would love dearly – if we were loved.

Renátó Fehér

Border strip

(1)

The love of railwaymen and pedagogues

for generation after generation,

on a short stretch of the western border strip.

As a piece of industrious labour always exemplary,

as an inheritance a disappointment that veers us to the right,

a paraplegic backbone.

They are all good Catholics:

Not a would-be suicide, fallen woman, or alcoholic among them.

Just the teach-them-a-lesson defiance of the little guy,

for which there is no reason or excuse.

Because the family lived as if there were a God.

And as for me, I learnt by myself how to believe in Him,

to be the first to question

the stories that were thought to be uninterruptable,

the first to be curious about the tiniest details,

the intakes of breath, the snores, the coughs.

Because it’s impossible to live saying: it’s OK as it is,

that crying together will solve everything.

And I grew up to speak with sentences

that must be said at proposals of marriage.

As if we were all to die the next day,

and it would at last be unecessary to keep on loving.

For this kind of thing they have no sense of moderation.

That they have blackmailed into me. That’s what they lost.

And at weekends in vain do they sob into the soup that

family comes first. By way of an answer

I swear by God that they’ll never see me again.

(2)

In the estuary of the allée of chestnut trees

the main building: a supertanker at anchor.

As one’s searching gaze lowers slowly,

it lands on a Roman numeral on the façade,

it would look into a cavernous room on the first floor.

What can be seen by someone inside, elbows on the ledge?

If he glances askance, a bay, else some foothills.

Back then boys here were trained to issue orders,

only through the thick jackets one couldn’t make out 9

how inside the ribcages, like fountain spray in frost,

valour had cracked.

Later the army-like column took

the stammering steps that became the city’s heartbeat.

There the fountain stands in the middle, but

of the parade ground there is no trace,

the wailing of those lined up in the fog

has died out of the park over the years.

Routine of cure replaced rigour of training:

limbs of ducks carve their way through

the tightly stretched surface of the water in the pool,

intakes of breath come wheezy and incurable,

thus does a hissing sound leak from the mouth cavity,

like wind through the allée.

And here crouches the ingatherer of the crop from the undergrowth,

silent, like a sign for tourists.

And even if in the end he couldn’t fit them all in his pocket,

he can recall every chestnut he picked up,

he can recognise, too, from its shape, its colour, its sheen, its damaged part

the one who looks after him,

it is from him tht he gets his face when he comes close,

he holds his hand when the class goes on a trip,

up and down on this border strip.

Balázs Szálinger

Hungarians

Mornings slipped on matters of colonization,

Foul-tasting teas, frosty fragrance, great sighs,

Damned vanillas on the kitchen shelf,

Century-old summer dust on unopened cans of our solutions’ arsenal.

As if a dark pine tree were sitting on the bed,

Willing us not to find a new direction,

Sprinkling our home with pine needles – smudging the place,

How far does the kitchen stone reach, and where does the steppe begin.

For the odd moment, now, amid wild clouds of dust

The populace wanders from here to over there,

As if the concept of landscape could be understood on the basis of the void,

And also why everything happened: perhaps we can transcend –

But it’s as if an eternal pine tree were sitting on the bed,

Angry vanilla-ed mornings await us aways,

Instead of the sodden floodplains,

The long fields awaiting breaking up,

Canaan flowing with milk and honey.

Márton Simon

H

That sense of how much better it would be

to be somewhere else, that was the most you could give me,

and did. The possibility of longing to get out of here.

The kind the child of an ex-empire doesn’t experience.

The kind only we can. It was worth it, even so, for the language.

Or, maybe, the other one, that here it’s the best. To each their own.

For some reasons, only the extremes. The places that

can be easily loved, those that will not be the death of you: those have gone.

This is what is meted out to us. To envision a fate whatever pothole we’re in.

To debate, howling, as we drown, whether in a reservoir or the ocean. Clouds homeward.

More than that who can give? Uncomfortable chairs,

a spritzer on a wonky table on the gravel.

Failures in slotting together tragic horizons. Eggs on our faces.

A self-image too grotesque to be even a caricature. World-patented silence.

Even so: rape fields over the centuries.

In the town where I was born, beside the bus stop

stands a statue on the scorched turf. A misshapen railing,

six storeys high, on it a few round mirrors. You held my hand,

I looked at the statue, I didn’t understand, I thought it was glorious,

I just didn’t yet know if it was you or me.

Of course, we can make a sad image of anything.

A landscape drawn in the vapour of a window of train arriving a thousand years too late.

The least you deserve is that I address you properly.

You, where the rule states only that it should have written on it

OPEN HERE, not that it should really open there, my homeland.